WAJDA

Exhibition: WAJDA

Venue: National Film Archive of Japan, Tokyo

Curatorial supervision: Hidenori Okada, Masao Fujiwara, Rafał Syska, Jędrzej Kościński

Project coordination: Dominika Górowska

Exhibition design: Tomasz Wójcik, Marta Gocał

Visual identity: Kaja Gliwa

Duration: 10 December 2024 – 23 March 2025

Co-organizers: Adam Mickiewicz Institute, National Film Archive of Japan

Partners: National Museum in Kraków, Polish Institute in Tokyo

Exhibition funded by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland, under the honorary patronage of the Minister of Culture and National Heritage, Ms Hanna Wróblewska

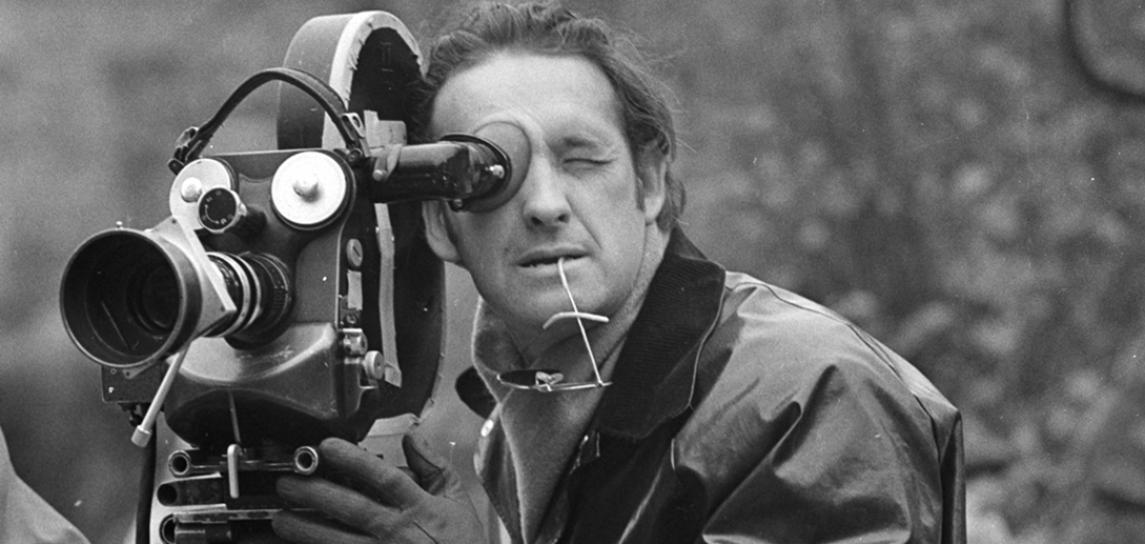

Starting in mid-December 2024, one of the heroes of Tokyo’s cinematic life will be Andrzej Wajda – Poland’s most prominent film and theatre director, recipient of an Oscar for lifetime achievement, known for such legendary films as Ashes and Diamonds (1958), Man of Iron (1981), Danton (1982) and Korczak (1990). An opportunity to become acquainted with this great artist’s work will be offered by a multimedia monographic exhibition held at the National Film Archive of Japan in Tokyo by the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology. The exhibition will be accompanied by a retrospective of Wajda’s films, co-organized with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute in Warsaw and the Polish Institute in Tokyo.

It would be hard to imagine an artist as versatile, universal, and fascinating to audiences around the world as Andrzej Wajda. Spanning from the mid-1950s to 2016, his career encompassed film, theatre, and painting, while linking the world of art to politics and extensive social activism. He made Polish cinema famous, taking inspiration from the aesthetics of other countries – notably from Japan.

Wajda was a classic filmmaker during his lifetime, a legend of the cinematic and theatrical arts. Even towards the end of his life, he continued to amaze with his creative inventiveness, and it was no coincidence that just a few years before his passing he received an award at the Berlin Film Festival for narrative innovation and blazing new creative trails in his film Sweet Rush (2007). A thoroughly Polish artist, he drew inspiration from Polish literature, painting, politics and historical events, but also from national mythologies, traumas, and phantasms; he nonetheless endowed his narratives with a surprisingly universal quality, actuating cultural codes common to all mankind, decipherable by viewers from all over the world. This gift made Wajda a cosmopolitan director, capable of making films and staging theatre productions in Poland, Russia, Israel, Switzerland, France, Germany, the United States, and Japan.

The intensity of Wajda’s works lies in the feverish emotion and dynamism of his metaphors. His films are composed of movement and space, a polyphony of voices and a mosaic of experiences. His sense of rhythm, his painterly sensitivity, his intuition in choosing his collaborators, and his impatience drove him to finish one project quickly in order to start another. Wajda was therefore active in film and theatre, was constantly drawing, incessantly writing in notebooks, discharged a variety of public activities, handwrote hundreds of letters, and made thousands of drawings in his sketchbook on every occasion. That is why, for this museum exhibition, we have had to devise an unorthodox space, full of nooks and crannies, images and sounds, editing ellipses, and a way to keep visitors in constant motion. Because this is the only way to capture the richness of Wajda’s untamed life.

The exhibition will primarily show objects from the Andrzej Wajda Archive, which is located at the Manggha Museum in Kraków. This is the starting point of the Tokyo journey that is charted by the director’s mementos: letters, sketches, production documents, and above all the notebooks that he wrote in every day for most of his life. This is how Wajda recorded his emotions, accounts of meetings, ideas for films, small joys, and ever-present annoyances. He would sometimes end his letters with a question mark because he never wished to make authoritative statements on values and opinions, preferring to express himself through uncertainty and hesitation. He often made drawings in these notebooks because sketching, drawing, and painting were his other passions, the earliest ones he had discovered in himself at a very young age and pursued by enrolling in the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków; subsequently, his work as a filmmaker moved these first passions to the margins of his artistic activity, until they regained their due power of expression in his final years. Wajda never created typical mood boards or storyboards; instead, he prepared graphic material for his films, drew the progression of the scenes, sketched the faces, and constructed tension by determining vantage points and cinematic perspective. Those drawn for some of his movies, such as A Chronicle of Amorous Accidents (1986), were true works of art, autonomous gems of artistic imagination.

His archive at the Manggha Museum holds several intriguing physical objects, among them props from the film Katyn (2007), including the rosary that the main protagonist is holding in his hand when he is executed by the NKVD on Stalin’s orders. There is also the costume worn by Kazia, one of the principal characters of The Young Ladies of Wilko (1979), played by Krystyna Zachwatowicz-Wajda, who, in addition to being Wajda’s wife, is herself a prominent set and costume designer as well as an actress. For decades, she stood by her husband and supported him in dozens of artistic and social initiatives. One of those was the creation of the Manggha Museum, an idea conceived by the Wajdas which became feasible thanks to the Kyoto Prize that Andrzej Wajda received in 1986, and which he donated to the construction of the museum.

The exhibition will also feature objects supplied by other institutions: production stills and BTS photos from the National Film Archive – Audiovisual Institute in Warsaw, posters from the Film Museum in Łódź, and costumes from the National Centre for Film Culture in Łódź and the Feature Film Studio (WFF) in Wrocław. The impressive collection of awards will be enhanced by loans from the Ossolineum in Wrocław and the Jagiellonian University Museum in Kraków: Wajda’s Honorary Oscar awarded ‘in recognition of five decades of extraordinary film direction’ and his Palme d'or from Cannes for Man of Iron (1981).

Clips from Wajda’s films will transform the exhibition space into a multimedia spectacle. They will be instrumental in building up the narration of the show and guiding visitors through it – from Wajda’s childhood in the Suwałki region and the romantic myths surrounding it; through the Inferno section, focused on the war, his New Wave experiments and the subject of revolution; to the nostalgia theme and the Japanese section.

When one explores Wajda’s films, it is hard not to realise what a genius he was. But it is also worth remembering that Wajda flourished when he was surrounded by excellent coworkers: when actors filled in roles that were not complete in the script; when camera operators turned his drawings and storyboards into explosive sequences of frenetic attractions; when composers were given an opportunity to express their flamboyant ideas in film scores. Directing means managing people, and keeping control over every aspect of the staging, both in film and in theatre. None of these processes, elements of the multilayered creative act, are visible when we view the finished film. Is this enough to really know a great artist? Or do we have to go behind the scenes and onto the shooting set, peek into the director’s sketchbook, read his notes, compare several versions of the screenplay, and take a look at those that never made it past the preparatory stages. Are this type of activities not the most intriguing path towards knowing a film and its maker? Such a narrative, in its polyphonic structure, can be provided by our exhibition on the work of Andrzej Wajda.